In 2019 Walford college merged with Hereford and Ludlow colleges to make North Shropshire college. In the same year Tom Moore became farm manager and was given the clear instructions the farm needed to be promoting best practice, high animal welfare and to break even financially. Tom didn’t feel that breaking even was best practice so set his sights on making the college farm as profitable as possible.

After looking at the financial performance of the farm in 2018 Tom knew that changes had to be made and quickly if he had any chance of making the farm break even let alone profitable. In 2018 the farm had lost £442,452, costs were high across all categories but purchased feed, bedding and machinery costs were exceptionally high. These costs were driven by forage quality and from this poor milk from forage (it was 985 in 2018), this resulted in large amounts of concentrates being fed. The dry and calving cows were housed in loose housing that were bedded up with straw, in 2018 the straw prices were high which helped to push the bedding costs so high. With all the machinery that was owned to undertake feeding, land care, slurry application, scrapping up, bedding and planting, the machinery costs were too high for this be of any benefit (as shown in table 1).

Table 1

|

Output |

£ |

p/l |

|

||

|

Milk |

394,864 |

25.70 |

|

||

|

Stock sales |

67,603 |

4.40 |

|

||

|

Other dairy income (excluding subsidies) |

|

0.00 |

|

||

|

Inventory change (automatically calculated) |

83,000 |

5.40 |

|

||

|

Total Output |

545,467 |

35.50 |

|

||

|

Variable Costs |

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

Livestock Purchases |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Purchased Feed |

|

||||

|

Total |

281,168 |

18.30 |

|||

|

Forage Variable Costs |

0 |

|

|

||

|

Fertiliser |

18,437 |

1.20 |

|||

|

Lime |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Seeds & sprays |

15,364 |

1.00 |

|||

|

Additives, plastic |

1,536 |

0.10 |

|||

|

Total |

35,337 |

2.30 |

|||

|

Livestock Costs |

|

||||

|

Vet & Med |

52,238 |

3.40 |

|||

|

Breeding, AI & Recording |

23,046 |

1.50 |

|||

|

Livestock sundries |

13,827 |

0.90 |

|||

|

Bedding |

121,378 |

7.90 |

|||

|

Parlour - Consumables |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Parlour - Service & Maintenance |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Total |

210,489 |

13.70 |

|||

|

Total Variable Cost |

526,994 |

34 |

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

Overheads |

£ |

p/l |

|||

|

Power & Machinery |

|

||||

|

Repairs & Spares |

75,285 |

4.90 |

|||

|

Fuel & Oil |

23,046 |

1.50 |

|||

|

Electricity |

10,755 |

0.70 |

|||

|

Tax & insurance (for power & machinery) |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Contractors: silage/forage |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Other contractors |

44,556 |

2.90 |

|||

|

Total |

153,642 |

10.00 |

|||

|

Labour |

|

||||

|

Paid |

156,716 |

10.20 |

|||

|

Unpaid (£30,000 per full time labour unit) |

0 |

0.00 |

|||

|

Total |

156,716 |

10.20 |

|||

|

Depreciation & Leasing |

|

||||

|

Plant, machinery, vehicles |

44,556 |

2.90 |

|||

|

Buildings |

21,510 |

1.40 |

|||

|

Machinery leasing |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Total |

66,066 |

4.30 |

|||

|

Sundry Overheads |

|

||||

|

Water |

9,218 |

0.60 |

|||

|

General insurance |

16,900 |

1.10 |

|||

|

Office, phone & bank charges |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Council tax |

12,291 |

0.80 |

|||

|

Advice & professional fees |

9,218 |

0.60 |

|||

|

Subscriptions |

|

0.00 |

|||

|

Miscellaneous |

24,583 |

1.60 |

|||

|

Total |

72,210 |

4.70 |

|||

|

Repairs land & buildings |

12,291 |

0.80 |

|||

|

Total Overheads |

460,925 |

30.00 |

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

Total Operating Expenses |

987,919 |

64.30 |

|||

|

|

|

||||

|

Cash cost (excl. depreciation & unpaid labour) |

921,853 |

60.00 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comparable Farm Profit (CFP) |

-442,452 |

-28.80 |

|||

Meeting the high animal welfare and best practise was also going to be an up-hill battle, with the rearing of the calves being the biggest issue. With no purpose-built building to rear the calves, they had been reared in various buildings on the farm like the old parlour. As these buildings were not designed with the required air flow for calf rearing, the calves suffered with high mortality rates. The feeding of the heifers post weaning was not giving them a balanced diet for growth and development, the effects of this can be seen through the breeding records for the farm. Each year the number of heifers that were mated >16 months of age was too high, with the average age at first calving peaking in 2017 at 29.9 months of age (as shown in table 2).

Table 2

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Age at 1st Insemination (months) |

14.8 |

15.8 |

15.7 |

14.8 |

18.0 |

16.2 |

19.6 |

17.9 |

14.5 |

16.1 |

16.8 |

14.2 |

|

Number of Young Stock not served >16 month |

42 |

49 |

38 |

37 |

58 |

49 |

53 |

85 |

36 |

39 |

38 |

17 |

|

Expected Calving Age Heifers |

24.3 |

25.3 |

24.7 |

24.6 |

27.1 |

26.1 |

29.7 |

28.4 |

25.3 |

26.1 |

25.9 |

28.4 |

|

Average age at first calving |

25.8 |

24.9 |

25.9 |

26.2 |

27.5 |

28.6 |

26.8 |

29.9 |

28.1 |

25.5 |

26.4 |

25.4 |

With a range of soil types, the farm can grow good levels of grass through the year and is suitable for growing maize which it has done, making the farm self-sufficient in its forage needed. The issue was that management of these forages resulted in poor quality silages. When coupled with the poor rearing of the heifers, the cows were limited in the level of production that they could produce. This saw the farm only being able to produce an average of 8344L/cow with a range of 7600L/cow to 9000L/cow, well below the genetic potential of the cows and what would be expected for the level of concentrates being fed (as shown in table 3).

Table 3

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Milking Herd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Cows in Herd |

126 |

143 |

193 |

219 |

224 |

216 |

225 |

216 |

214 |

153 |

140 |

153 |

|

Average 305 days production milk |

8050 |

8580 |

8357 |

8612 |

8707 |

8509 |

7621 |

8594 |

8421 |

9018 |

7635 |

8022 |

Knowing that improvements needed to be made quickly for the college farm to remain, Tom drew on his prior farming background knowledge to formulate a plan to improve the situation. He proposed that the college turns the cows out to grass and move the system to an autumn calving block. The college backed this plan with the only stipulation being that the current herd remains and the future breeding retained a black and white cow, with a new principal instated in 2020 these rules were relaxed.

The plan for improving the financial performance of the farm focused on cutting costs as well as increasing the income. Through turning the cows out and targeting 9 to 10 months of grazing, the farm will be able to lower the amount of purchased feed along with the requirements for silages to be grown and made. The goal is to get the concentrate use down one tonne per cow through maintaining good grass quality year-round and make high quality silages. Another measure for success here would be to achieve 6000L from forage. The creation of the autumn block will better match the grass growth on the farm with the demand from the cows as well as giving the herd uniformity in their dietary requirements. At the beginning of the transition the average age of the herd was 2.3 years, the aim is to increase this steadily up to the target of 4.5 years, to achieve this the heifers needed to be properly grown when they enter the herd and target 95% of them making it through to the second lactation. Luckily the creation of the block and turning the cows out freed up the dry cow shed to be used for calf rearing which has fixed the calf mortality issue.

The farm was originally supplying Müller on a white-water contract with a slight bonus or penalty around the percentage of fat. At the beginning of the transition, this milk contract was one of the lowest paying on the market. With this milk contract, maintaining milk production through the transition was important to minimise any loses. Changing the milk contract to one that would see a greater value per litre was needed, the aim was to get onto a milk solid based contract as this wouldn’t result in less income if litres were exchanged for higher solids. As the farm was unable to obtain a solids-based contract through Müller, they have now changed to Helers cheese. To be able to make the most of changing the milk contract, the percentage of fat and protein in the milk needed to increase, the breeding would need to change to achieve this.

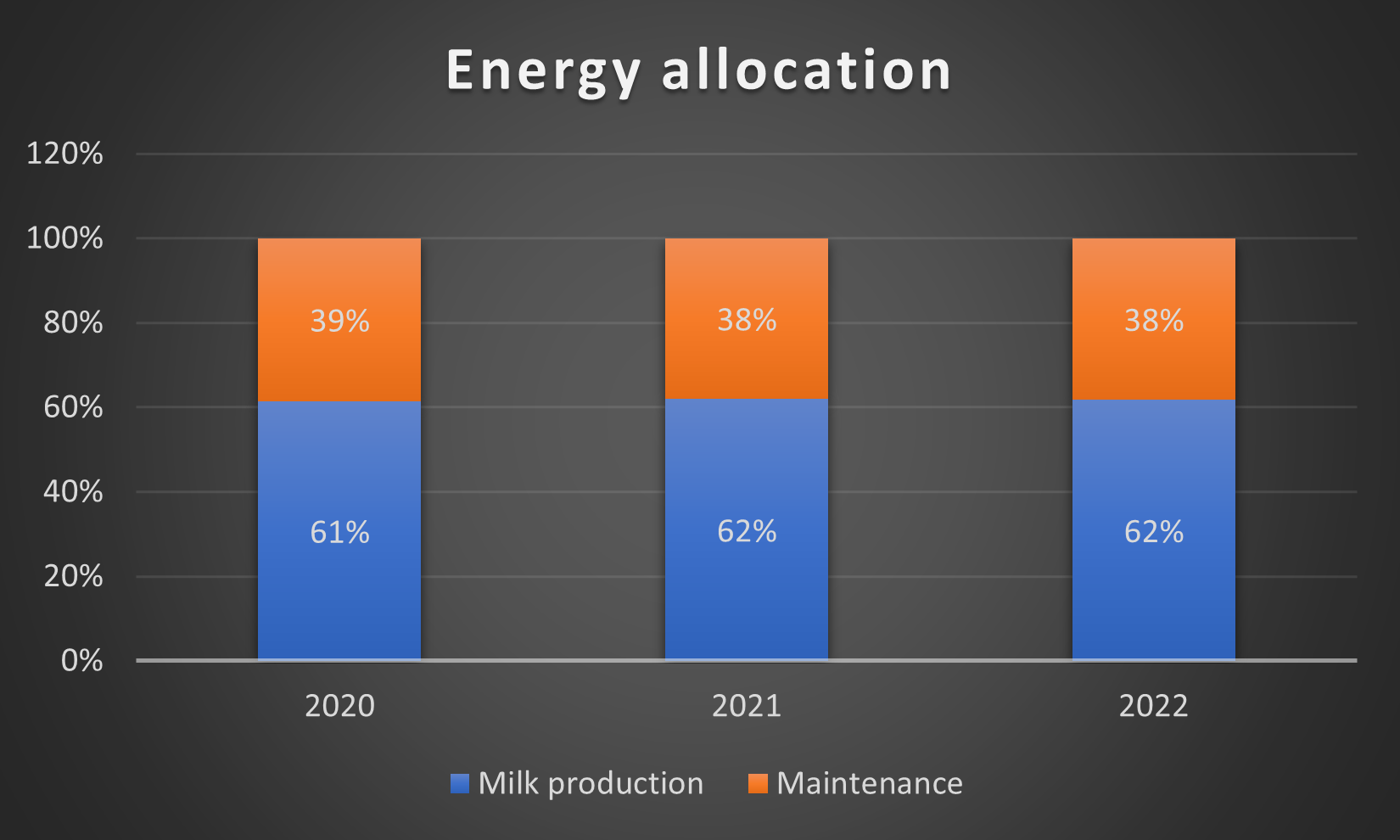

To be able to achieve the goals stated above, the type of cow being farmed needed to change. To be able to maintain grass quality with minimal mechanical intervention, the cows need to be effective grazers. Despite the Holsteins proving that they can be trained to achieve constant residuals of 1500KgDM, they were not able to graze above 15KgDM of grass per day without becoming unsettled. So, to be able to get more grass into the diet, grazing cow genetics were needed. This need for grazing genetics was also highlighted in the first summer of grazing when the fat % in the milk dropped to 3.3%, the Holsteins were affected more by the waxy coating on grass, meaning they cannot access the fibre as easily. As cows are limited to 18KgDM of grazed grass intake in a day irrespective of the breed, the maintenance requirements of the cows needs to be as low as possible to enable the maximum energy to be put towards milk production. The Holsteins in the herd averaged around 680Kg, meaning their maintenance requirements were 78MJME, if the cows had met their genetic potential their maintenance could have been as high as 85MJME. The target is to reduce the herd size down toward 550Kg, this would reduce the maintenance requirements to 65MJME. This means 2 litres worth of energy is no longer going towards maintenance and can be put towards milk production. With the furthest paddock being 1km away from the parlour, the cows would need to have feed and legs that can withstand the requirements of walking to and from the parlour twice a day. To lift the fat and protein levels, this needed to be a key selection criteria for the selection of bulls along with fertility to be able to retain a tight block.

Graph 1

Through crossbreeding these gains will be maximised from the hybrid vigour that will be obtained. When breeding within breed, the potential of the heifer is taking half of the cow and half of the bull’s traits, but when you are crossbreeding the parent traits are increased by the below factors.

Table 4

To be able to receive 100% of these benefits from hybrid vigour, the cow and bull need to be of different breed e.g 100% Holstein cow and 100% Jersey bull. Breeds like Ayrshire and Holstein are closely related so the level of hybrid vigour is going to be less. Research in New Zealand around grazing cows found that the best cross was between New Zealand Jersey and Holstein Friesian, Jersey’s and Ayrshire’s are genetically further apart but the lower production figures of the Ayrshire’s negated the slightly higher level of hybrid vigour.

With the breeding stipulations placed on the farm around maintaining a black and white herd, the opportunity to obtain hybrid vigour was reduced. The bulls used in the first year were hammer and Kelsbells both of which are F15J1 breeding along with Sierra F11J5 and Beaut F9J7, as the New Zealand Holstein Friesians are 8 generations or greater removed from the breeding historically undertaken at Walford, this meant that each bull would provide some degree of hybrid vigour.

Table 5

In 2020 with the change of the principal, the farm was open to using any breed. The Jersey bull integrity J16 was used for the first time over the Holsteins, this bull brought 5.9% fat and 4.3% protein, longevity and low live weight. The benefit for the heifers from this breeding is that no matter which bull is used on them there will be 50% hybrid vigour, this allows for a wider selection of bulls to obtain the type of cow that is being targeted on the farm.

The move to a grazing autumn block system has proved to be the right decision for profitability, the results from the breeding is only in its first year with the first lot of LIC bred heifers entering the herd in 2022. These heifers have calved down around 580Kg meaning they will likely reach a mature weight of around 640Kg. This is not much below where the herd was originally, but this is due to the cows not meeting their genetic potential. From the milk recording data taken so far this year, the heifers are outperforming the herd on fat and protein percentages, the heifers are averaging 4.38% fat and 3.33% protein with a range of 3.36% to 5.87% for fat and 2.77% to 3.8% for protein whereas the average for the herd is 4.32% fat and 3.29% protein. The heifers are averaging 21.7L so are on target to meet the current herd average of 26.2L when they reach maturity in their fourth lactation. Now the herd is in a single block, more selective breeding can be undertaken, this hasn’t been an option currently as the creation of the block required every cow to be mated with a dairy straw and calves kept ensuring enough replacements were obtained at the front of the block. This selection pressure will see more heifers entering the herd with fat and protein percentages around the 5.8% and 3.8% instead of the 3.3% and 2.7%.

The Holstein Jersey cross calves were born around 15Kg lighter than previous generations out of the Holsteins which is promising for decreasing the average liveweight of the herd. With the litres from the mother, the fat and protein percentages from the father and with 100% hybrid vigour the potential efficiency of these heifers is huge and in 2023/24 we will be able to see how they stack up against their mothers and pairs within the herd.

Photography Credit @Jenny Wood Photography