When considering the performance, welfare and profitability of commercial suckler herds, it is not controversial to state that bad calvings are a bad thing, nor that a systematic approach to reducing bad calvings delivers significant benefits across all these fundamental aspects. Yet this issue, until recently*, has remained below the radar, with many suckler farmers appearing to accept as inevitable the frequent need for assistance at calving and the associated losses.

However, there is ample practical experience to challenge this traditional way of thinking. Suckler herds that have put an emphasis on tackling the causes of assistance at calving have brought about profound changes and demonstrated that they can go year after year with all their cows and replacement heifers calving entirely unassisted. They discover that their previous tolerance of bad calvings had deep pernicious consequences for their herd and themselves, the removal of which not only reduces deaths, illness of livestock etc, but that the range of unexpected benefits across the enterprise makes running a suckler herd an altogether more positive experience.

Consequences of assisted/bad calvings

Major financial and welfare losses arise from bad calvings, this list is not exhaustive. Perhaps part of the reason why farmers under-estimate these is because many take their toll long after the calving.

For the calf – death, injury, illness, stress, weakness, insufficient colostrum intake, unthrifty, needing special treatment, out of its group.

For the cow – death, injury, illness, stress, rejects calf, fails to rebreed or gets out of pattern, overly fat, culled early.

For the herd – more complicated management (pens of special needs), risk of disease (more replacements needed, or calves brought in to suckled on), disrupted block calving, more vet interventions.

For the farmer – (death, injury, stress), lack of sleep, inefficient working, impact on family life, depression, disappointment, loss of ££££ from all above, more ££££ for cameras, monitoring, special feeding.

Causes of assistance at calving

These fall into three broad categories:

- big calf stuck in small pelvic area of heifer/cow

- malfunction of the natural calving process, e.g., malpresentations, issues with twins

- farmer unjustified worries or impatience

The first category is essentially a mismatch between the birth weight of the calf and the size of pelvic opening in the heifer/cow. It is avoidable as these result directly from the breeding decisions made by the farmer. Following the action plan below will remove this as a cause of assisted calvings.

The second category is rare, and largely unavoidable. However, following the action plan will mean that less of them will be observed as the cow will calve more of them without assistance.

The third category of unnecessary farmer intervention is provoked by the amount of assistance needed in respect of the first two categories, the reduction of which (from following the action plan) will give the farmer more confidence to let well alone.

Action Plan to reduce assisted calvings in commercial suckler herds

The four pillars of the plan are:

- change suckler farmer attitude to assisting calvings

- ensure breeding females have adequate pelvic openings

- select sires to give appropriate calf birth weight

- account for the adverse impact that variants of myostatin gene have on breeding females

The best results are obtained when all of these are taken on board and become permanently part of the ongoing breeding policy.

Farmer mindset towards assisted calvings

This is the most important element of the action plan. The suckler farmer needs to be intolerant of assisted calvings and recognise that any assistance = loss, that it is not okay to go and give a “gentle tug” just because you can see the calf’s hooves and to be disciplined to keep out of the calving pen until it is time to tag the calf. Breeding for calving ease must be given a high priority.

Pelvic area of breeding females

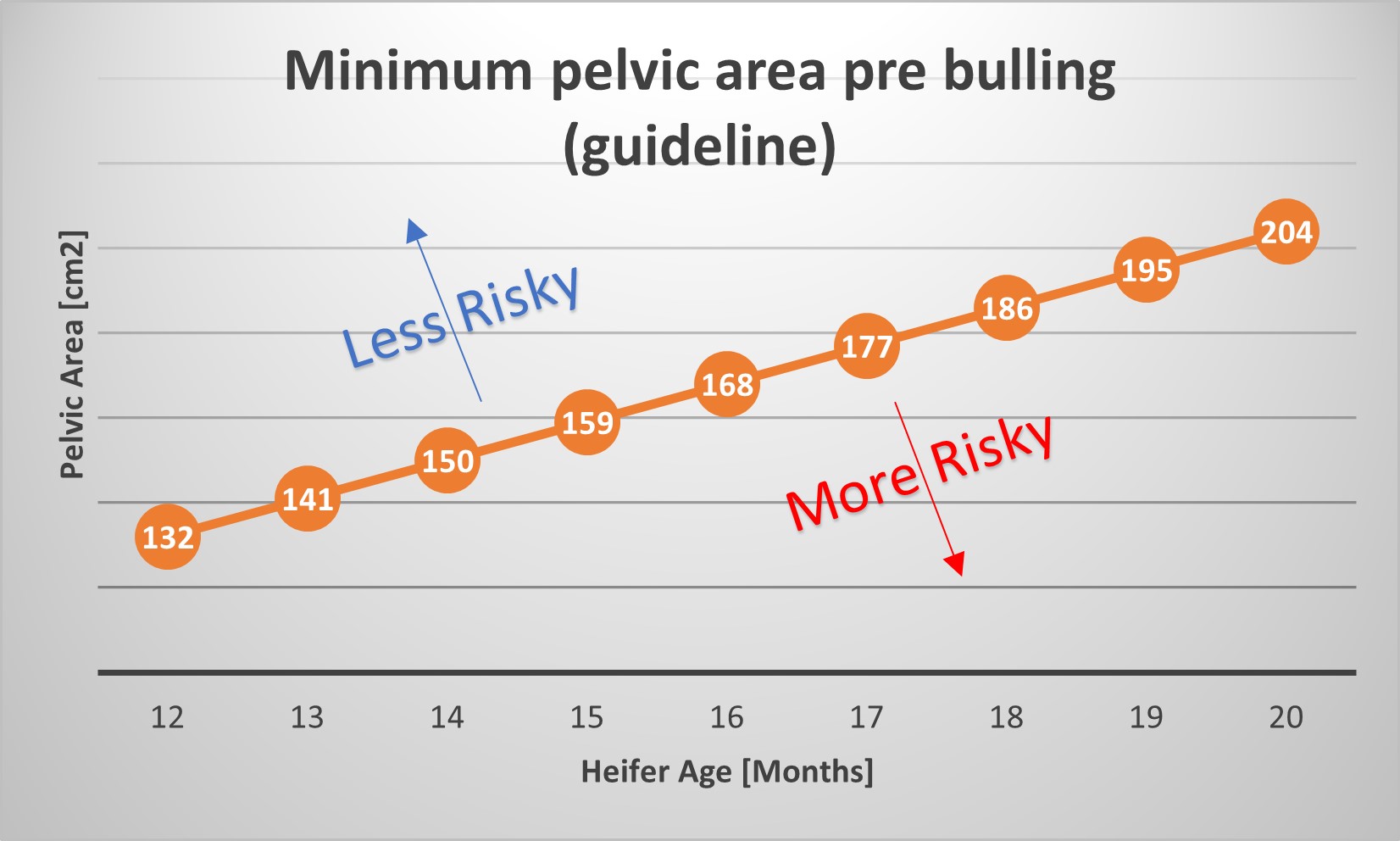

Heifers, selected as potential replacements, should have their pelvic area measured prior to service to assess that it is sufficiently large for the expected birth weight of calves by the sires used in the herd (see figure 1).

Pelvic area cannot be assessed from any external feature or trait and must be measured directly (internally) using a pelvimeter.

In the author’s experience, Salers heifers make excellent replacements (the Salers is noted for it’s very large pelvic area), nevertheless there is sufficient variability of pelvic area within all breeds to provide scope for rejecting the smaller pelvic area heifers from the group of intended replacements.

Figure 1: Guideline to the minimum pelvic area pre bulling

This guideline has been developed from original research done in the USA in the 70’s and 80’s (Deutscher and others) and adapted to typical UK sucklers. It is being used successfully by a growing number of vet practices over recent years.

Pelvic area is a threshold trait, meaning the objective is to breed females with a sufficiently large pelvic area to permit unassisted calving, but there is no benefit to going beyond this to breed females with ever larger pelvic area.

Bull pelvic area can be measured the same way as heifer pelvic area, and as pelvic area is a strongly heritable trait, for those breeding their own replacement heifers the use of a known large pelvic area bull will predictably increase the average pelvic area of his daughters. For reference, the Salers bulls in the Rigel herd are all pelvic area measured by a vet, and average 200cm2 at 400 days.

Calf birth weight

In this aspect at least, there is plenty of advice for farmers elsewhere, but in a nutshell, select breeding bulls to use on your replacement heifers with predicted low calf birth weights. Look for high accuracy EBV (>90%) and aim to source bulls from performance recorded herds, ideally where all/most animals are recorded.

The undesirable factor of heavy birth weight and the desirable trait of strong growth rate normally go together, so this is a question of balance. If your females have large pelvic areas, then you can use bulls with heavier birth weights to obtain stronger growth rates.

It is very helpful to weigh calves at birth to confirm that the sire EBV is a good predictor in your herd. For reference, with an average gestation of circa 283 days, the birth weights of Salers heifers are 32-36kg, and Salers bulls calves weigh 36-40kg.

Myostatin in suckler cows

The nine known variants (mutations) of the normal myostatin gene confer, to varying degree, important advantages within the terminal sire breeds (double muscling etc). Unfortunately, these variants also confer disadvantages on key maternal traits, again to varying degrees, including reduced calving ease, reduced fertility, reduced milk and reduced ability to convert forage.

For commercial suckler herds, to achieve the maximum advantage from using strongly muscled terminal sires with 1 or 2 copies of these variants, then the cows should be known to have 0 copies. Striking this balance protects the benefits of having a milky easy calving fertile dam who can maximise (off grass) the growth and conformation of her calf.

What outcomes can be achieved?

In short, a great reduction in the financial losses and welfare issues from the bad calvings listed above, which taken together transform the life and work of the suckler farmer. Looking beyond the benefits to the individual farmer, the significant gains in fertility, longevity, productivity and efficiency available if more suckler herds incorporated this approach would all contribute to reducing the “carbon” per kg of beef produced by our industry.

For reference, the calving performance of the Rigel herd of pedigree Salers over the 21 years from 2002-2022 is as follows:

- Cows, 1581 calvings, 17 assisted (1.1%), with 4 of the 17 requiring the vet including 1 caesarean.

- Heifers, 288 calvings, 4 assisted (1.4%), no vet assistance required.

(*) the recent campaign by AHDB (Maternal Matters)

Photography Credit @Jenny Wood Photography