This article was written by Rhian Price, press officer for the British Cattle Breeders Club.

Farmers deliver multiple public goods to society, not just net zero, and it is important this message is articulated to and recognised by society.

These public goods include producing nutritious food, delivering soil improvement, accelerating carbon sequestration, improving water quality, optimising biodiversity and generating profits.

What is Net Zero?

Net Zero is where the sum of emissions equals the sum of sequestration after it has been adjusted for fossil fuels displaced by renewables and methane emissions reduced by waste management.

Net Zero is not about zero emissions, zero emissions mean no animals nor humans.

The ARC Zero project – results and future aims

Arc Zero is a project led by a cross-section of seven farmers in Northern Ireland who wanted to establish a baseline of carbon stocks and emissions and benchmark their businesses with their peers.

To achieve this, we baselined emissions, measured carbon in trees and soils accurately (using aerial LiDAR Surveys to create a carbon asset register and by measuring soil organic carbon down to one meter), estimated carbon sequestration and reached a net carbon position. This new knowledge empowered behavioural change on all seven farms.

Results

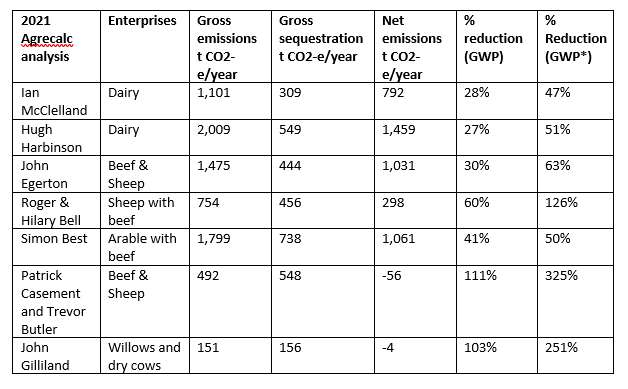

On all seven farms, every farm’s net position was better than its gross position (see table 1: Emissions of the seven farms).

Results show that no two farms are the same and there is no silver bullet on this journey.

Table 1: Emissions on the seven farms

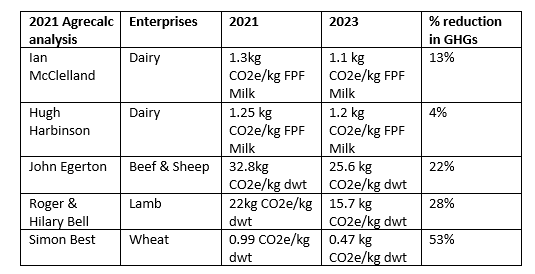

Table 2: Comparison of farms between 2021 and 2023

The reduction in GHGs on the livestock farms were far greater when they were reported using GWP* in comparison to GWP100. This is because GWP* recognises methane is a short-lived gas (see table 1).

So far, when using GWP* three farms out of the seven have reached Net Zero.

The UK Net Zero target is for the sector to get to zero, not individual businesses. I envisage that by 2050, some farms will have gone way beyond net zero, and others won’t, and there will be some sort of trading scheme to equal that out (akin to milk quota).

Carbon stocks and future project aims

Across the seven farms, there were half a million tonnes of carbon stocks. On the seven farms, 97% of carbon is in the soil, not in the trees.

As we race to get rid of animals and plant trees, just remember one thing: it is the soil you must look after.

By 2027, the seven farms want to build carbons stocks (from 515,166t of CO2e to 530,000t). The challenge to policy makers and scope three declarations, is will they be sophisticated enough to pick up that increase of carbon? Currently, improvements are not reported and this needs to change.

What lessons can be learned from the project and how can farmers reduce emissions?

There is a big toolbox of solutions available, but it is vital you know your own numbers and prioritise the solutions which are most cost effective for your business.

Some examples include:

- Improving efficiency is a win-win both for the environment and business profitability. Improving genetics, reducing age of slaughter and cow size; and improving animal health are all low-hanging fruits.

- Soil pH. Livestock producers are not good at keeping soil pH up, and if you are interested in legumes, up means 6.5 because that allows you to sweat legumes and herbs and dramatically reduce nitrogen fertiliser use.

- Reducing nitrogen fertiliser: Nitrous oxide emissions are the easy wins, not methane (methane is the expensive one to look at).

- Planting trees and hedgerow management

- Grazing willow (there was a 28% reduction in greenhouse gas intensity per kilo of liveweight gain at my own farm by grazing willows).

- Installing renewable energy.

Delivering multiple public goods

Using the LiDAR survey data to create run-off risk maps to analyse where water and nutrients leave farms during heavy rainfall can help identify where to place land management mitigation such as multi-species swards and woody riparian strips.

Multi species swards help improve water infiltration, build carbon, and simultaneously reduce nitrogen inputs. It is an example of how one change (sowing multi-species leys) delivers multiple public goods, and this can be measured.

Faeces help improve soil biodiversity. Observations on my own farm show earth worms, soil respiration rates and bacteria and fungi biomass are greater on land where cows graze.

Next steps

The Soil Nutrient scheme in NI aims to test all fields, trees, and hedges over four years to help farmers manage nutrient applications and create a baseline for carbon stocks and run-off risk maps.

Since it opened in May 2022, 92% of farmers have entered the scheme.

This is a public good and the government should pay for it. We secured this in Belfast, and I hope we can do the same in Cardiff, London, and Edinburgh.

How do we change the narrative?

Know your numbers to change the narrative. Our new environmental strategy will rely on that.

We are not on this journey alone. On the back of COP last December, The United Nations Food Agricultural Organisation published its roadmap to deliver zero human hunger and 1.5 deg temperature rise by 2050.

It is about tying human hunger and agriculture together. What you can see from the report are some interesting challenges; they are asking for a productivity increase of 1.7% every year until 2050. That is not a message that we are a sunset industry.

They also want to see an increase of 10 gega tonnes of carbon sequestered in crop and pastureland.

It is up to us to decide what we want to do and play a role in delivering that 2050 vision. But it won’t happen unless we baseline, measure and manage with forensic integrity, put power back in farmers’ hands and lead and are not led.